Kudos to Shapr3D for reprinting on their website the book, The History of CAD, by Dave Weisberg:

https://www.shapr3d.com/blog/history-of-cad

Weisberg was there at the beginning at MIT in 1957. The book documents the CAD industry up until about 2007. Not all of it, as the author says, but what’s covered (so much) documents with fascinating depth. The personal stories, the connections among the people who did this work, the invention of fundamentals that make things work, that give us the applications we take for granted these days, and the functions within them. The people who did these things have names. Weisberg knew them.

You probably know their names too, many of them show up in our CAD tools, the functions they built often eponymous.

It’s a remarkable document to say the least.

The book touches on things that are formative in our lives. I’ve had the honor to work for some of the people whose stories are told in the book. But it’s even more basic than that. I’ll start in 1980, with this:

Watch that video. I love this guy. He totally captures the spirit of a generation, in my opinion. If you review this game, Missile Command, this is exactly how you should do it. It can’t be done better.

The trackball

The game came out in 1980. I was in the arcade that year, age 13, dropping quarters to give it a go. The trackball made an indelible impression. It’s just, very tangible.

7 years later, I was on this ship, also launched in 1980…

…operating this equipment https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Naval_Tactical_Data_System (NTDS):

While there’s more to say, it’s all said at the link. I just add that these consoles had a trackball, which you can see if you zoom in, just to the bottom right of the circular radar screen in each console. The guy seated at the center (not foreground) of the image has his hand in that pocket, over the trackball.

It may interest you to know:

- These NTDS consoles, pictured above in 1940, looked pretty much esactly like that when I used them in the 80s and 90s.

- One of the uses of the trackball was to allow the user to modify the position of overlay graphics which were to be kept aligned with radar graphics, of ships and aircraft detected within the radar radius (~60 miles in our case). This of course was partially automated, and by the late 80s, fully automated on the newest ships. But human eyeballs were still in the loop when I was doing this. And the trackball was the interface, and a particularly good one.

- And yes, the connection with the arcade game was lost on no one.

Origins of CAD

See Weisberg’s chapter here: https://www.shapr3d.com/history-of-cad/computer-aided-designs-strong-roots-at-mit These radar consoles, their graphics, sensors, networking, real time interactivity, and so on, are at the origin of what would later become the CAD industry.

For terminology (“CAD”), I appreciate the reminder in the introduction:

“For simplicity, I have decided to refer to this industry as Computer-Aided Design or CAD rather than use all the other acronyms that are applicable to specific aspects of the technology such as CAE for ComputerAided Engineering, EDA for Electronic Design Automation, CAM for Computer-Aided Manufacturing or PLM for product Lifecycle Management. I have included an appendix explaining much of the nomenclature applicable to the material in this book.“

Either it would be useful, or it’s just a nagging personal preference of my own alone, for the industry to slow the proliferation of new terms / names for the same thing and return instead to simpler more generally applicable words.

Computers are so old, and ubiquitous now that the C could rightly be dropped from these terms altogether, and the A. That something is “Computer-Aided”, is by now already long ago a “who really cares” moment. It mattered in 1947, and 1967, and even 1997. But now? It doesn’t matter.

I’m particularly interested in the words drawing and modeling.

Drawing and Modeling

After the Navy I had no idea what to do with myself. I was interested in pretty much everything and nothing. We still had public universities back then in the United States, so I had the luxury to mess around and try different studies. I tried a few and nothing stuck until I tried Architecture school. That, I actually finished.

Glad I did. It was an intellectual exercise.

I wasn’t the best student but I took the material seriously. Enough that I put a lot into thinking about it, trying to understand it more than superficially. This is not directly correlative with producing the best grades, or the best work. That came later for me, after school.

The fun was over then. I had to work. And anyone who works in this industry knows the often overwhelming stress of dealing with projects, deadlines, enormous production requirements, huge knowledge requirements, regulatory issues, quality issues, let alone anything to do with the pressure of designing anything with at least some charisma.

And on top of all of this, the relentless difficulty of dealing with computer software in the production of your work in Architecture, Engineering, and Construction.

Just the other day I saw a video clip on Linkedin about the stressful life of steel detailers. I think others can relate. These professions can take their toll on your physical and mental health.

Software is supposed to help with this though, isn’t it? It’s suppose to reduce drudge work, and so on (the usual promises).

Well, here’s an analogy that some might not expect but many will appreciate

Software in AEC can be like a tractor pulling sled. Like the sled in a tractor pull, the farther you pull it, the harder it is to pull. Likewise, the more skilled you are at using software, the more you use it, the more you rely on it, the harder it pulls back, against your progress.

It’s not a perfect analogy but many will recognize it. Many who’ve done high powered use of software in AEC understand this.

For those who never lived in a rural environment and have no idea what a tractor pulling sled is:

THE FARTHER THE TRACTOR PULLS THE DRAG, THE MORE DIFFICULT IT GETS.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tractor_pulling

Truck and tractor pulling, also known as power pulling, is a form of a motorsport competition in which antique or modified tractors pull a heavy drag or sled along an 11-meter-wide (35 ft), 100-meter-long (330 ft) track, with the winner being the tractor that pulls the drag the farthest. Tractor pulling is popular in certain areas of the United States, Mexico, Canada, Europe (especially in the United Kingdom, Greece, Switzerland, Sweden, Netherlands, Belgium, Italy, Denmark and Germany), Australia, Brazil, South Africa, Vietnam, India and New Zealand. The sport is known as the world’s most powerful motorsport, due to the multi-engined modified tractor pullers.

All tractors in their respective classes pull a set weight in the drag. When a tractor gets to the end of the 100 meter track, this is known as a “full pull”. When more than one tractor completes the course, more weight is added to the drag, and those competitors that moved past 91 metres (300 ft) will compete in a pull-off; the winner is the one who can pull the drag the farthest. The drag is known as a weight transfer drag. This means that, as it is pulled down the track, the weight is transferred (linked with gears to the drag’s wheels) from over the rear axles and towards the front of the drag. In front of the rear wheels, instead of front wheels, there is a “pan”. This is essentially a metal plate, and as the weight moves toward it, the resistance between the pan and the ground builds. THE FARTHER THE TRACTOR PULLS THE DRAG, THE MORE DIFFICULT IT GETS.

Tractor pulling originated from pre-Industrial Era horse pulling competitions in which farmers would compete with one another to see whose teams of draft horses could pull a heavy load over the longest distance. The first known competitions using motorized tractors were held in 1929 in Missouri and Kentucky. Tractor pulling became popular in rural areas across the Midwestern and Southern United States in the 1950s and 1960s. From there it gradually spread to Canada, Europe, and Australia and New Zealand.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tractor_pulling

I was going to talk about drawing and modeling, and I’ll get to that, but I digress a little more now that I’ve started.

Someone should write another book, not about the history of CAD, but about what happens when you use these tools. What happens to YOU, and your projects.

Of course, of course, such a book would include success stories, accounts of many triumphs in the use of software tools. But an honest account would include the failures too, and the costs along the way. Countless people could be interviewed who’d be relieved to convey, and have acknowledged, the suffering endured because of inadequacies, failures, shortcomings in software, particularly as these are paired inevitably with altered expectations that always come with the choice (?) to use the tools in the first place.

How many of us have been in the office at 3am in desperation, AGAIN trying to overcome obstacles, put up by the software itself impeding progress on what we said we could deliver specifically because of these tools?

We again are responsible for making results happen AT ANY COST because we’re the ones who championed the tools to begin with.

END OF DIGRESSION

Models and Drawings.

If you follow people working in AEC (architecture, engineering, construction) on Linkedin or various forums, you might find people having difficulty defining these words these days.

Just one example, last week I saw a discussion about models without geometry.

That auto-prompted for me the memory of a saying:

Without Geometry, Life is Pointless

– David Fouche

Jokes can be lost in translation though, so, another lesson learned.

Simple, useful definition:

Model and drawing are related to each other in simple, direct ways.

A model is an environment.

It spans space and time. We engage with it visually, and in other ways, but primarily, and first, visually.

A drawing is an instrument for visual close study.

I know this, beyond superficial knowing, from first hand experience producing mental models, digital models, technical drawings for construction, and model-automated drawings for the same purpose, under pressure and deadline, for years.

Because I was ‘expert’ in software usage for this output, with the expertise coming from bullheaded determination, and because I was outspoken in both praise of the software and calling out its faults (because I needed the faults fixed), I ended up working at the software company who’s tools I used.

From that experience and everything connected with it, I’m reading Weisberg’s The History of CAD with pleasure. It’s very well written, the stories well told, including hints of the drama (it’s an industry of personalities, and battles), and the technical challenges (users weren’t the only ones challenged).

It’s the story of people solving immediate problems. It started with gunnery trajectories in the Navy. It developed into mathematical description of complex surfaces in ship and aircraft building and automobiles. And it just moved on and on from there (COGO, DTM, photogrammetry, just to name a few).

Something I did in the CAD industry

Let me add something I did in the CAD industry. Weisberg’s book ends in 2007, the year I wrote up a proposal for new development, sent it to the people responsible for the tools I used, and from which I was hired at the company I so admired (though their tools made me suffer too).

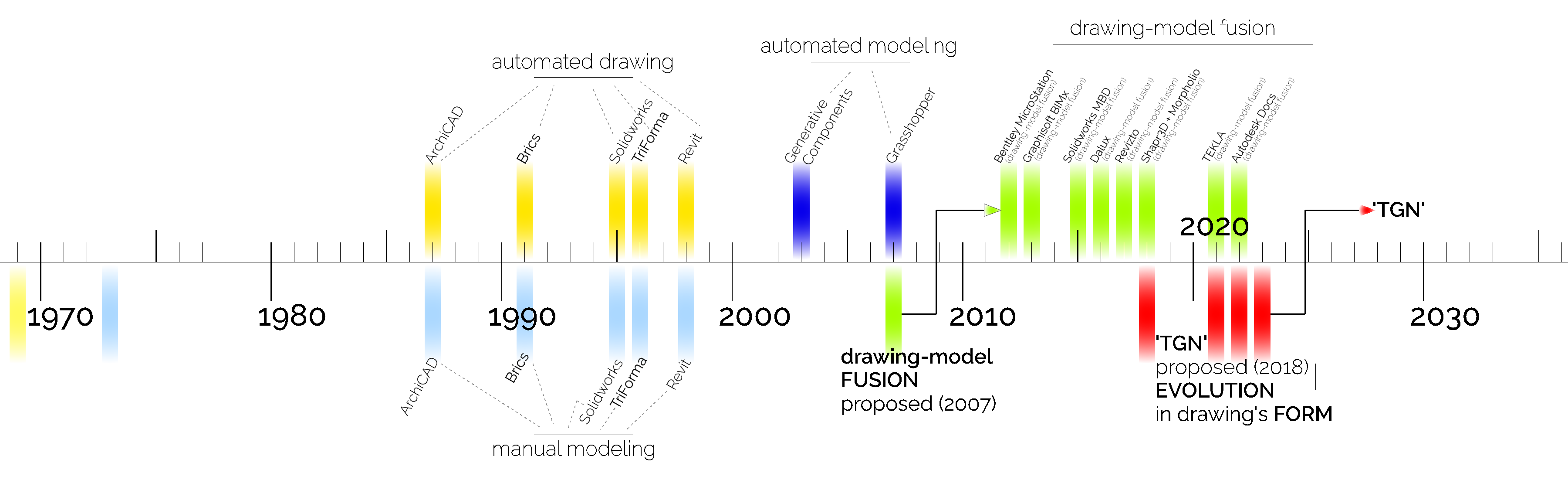

That was the drawing-model fusion proposal in green on the graph here (the lower green bar, 2007):

This graph is skewed toward my particular interest. It just marks a few of the originating items from the 50s, 60s, and 70s, from Weisberg’s book. There are thousands of discoveries, inventions, and products that can be added, all covered in detail in the book, and much more not in the book.

I’m just calling out some of the apps that were prominent in my part of AEC and that played a big role in the transition:

- from manual drawing creation (light yellow) in CAD, to automated drawing (dark yellow)

- and from manual modeling to automated modeling (dark blue)

The green bars are something I contributed

As I mentioned, drawing is for visual close study, of environments (of models). That’s not something to be dispensed with. It’s more important to conceptualize and actualize visual close study in terms of FUSION. Which is what I proposed.

I led the team that first developed and commercialized the automated fusion of technical drawings in-situ where they actually are within digital models (the first green bar above the timeline, in Bentley MicroStation).

That’s been taken up since then at 9 software companies that I know of.

But that should not be the end of the drawing-model fusion story, because, as I say on the front of my website,

Just as drawing is for close study (of mental models), TGN is for close study of digital models.

As much as people argue for what sounds fashionable, to kick drawing down the back stair into the dustbin of history, that particular idea is counterproductive at best. Thoughtless nonsense is another way of putting it, and not even close to the least charitable, and accurate, way of describing the notion.

I always say,

Why continue missing the point?

Drawing is not, and is not about, flatness. What it’s about, is visual close study. Call it VCS if anyone wishes.

The equipment for visual close study (VCS) traditionally for centuries, has been technical drawing. The form of drawing’s expression came to be what it is, during the centuries predating digital models, when models were MENTAL models (and physical).

The transition from MENTAL model to mental AND DIGITAL model is a megatrend

Because it’s a megatrend, it should induce a corresponding transformation in the form of expression of Visual Close Study.

I write about the nature of VCS in AEC on my blog here:

I propose, specify, and mockup/demonstrate the proposed continued evolution in the form of expression of visual close study (VCS) in digital models of ALL kinds, at my website: https://tangerinefocus.com

While I first made my FUSION proposal in 2007, and that worked its way to some extent so far, through the industry, this new proposal, TGN, the red bars in the graph above, I’ve worked on since 2018, and no one has yet taken it up in development.

But they will.

Because the development is necessary.

Everyone needs equipment for visual close study of very complex digital environments.

The green bars in the graph above, indicating the fusion into digital models of drawing in its centuries old form, a form that embodied visual close study of mental models to the extent made possible by mental models, is not enough.

Digital models themselves demand evolution in the form of this function.

This is the motivation for the TGN proposal (the red bars in the graph).

The form and function of visual close study are well served by the TGN proposal. It’s at the least a significant step forward. And it will make software less of of drag on work, should make software less of a tractor pull sled like this:

I remain at the service (call me) of any software organizations that would like my participation in their implementations of EQUIPMENT FOR VISUAL CLOSE STUDY OF DIGITAL MODELS OF ALL KINDS.